- Home

- Octavia E. Butler

Survivor

Survivor Read online

All of the characters in this book

are fictitious, and any resemblance

to actual persons, living or dead,

is purely coincidental.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Butler, Octavia E

Survivor.

I. Title.

PZ4.B98674Su [PS3552.U827] 813'.5'4

ISBN: 0-385-13385-5

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 77-81548

Copyright © 1978 by Octavia E. Butler

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition

Contents

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER ONE

Alanna

I didn’t know enough to appreciate my foster father the way I should have when we met back on Earth. That was when I was about fifteen and his Missionaries caught me stealing from their cornfield. They shot me, would have killed me, but he stopped them. Then he carried me back to his house, got a doctor to tend my wound, and announced that he and his wife were adopting me. Just like that. I heard the doctor try to talk him out of it when they both thought I was unconscious.

“You could be making a mistake, Jules. She’s not the harmless young girl she appears to be. And she’ll never replace your children.”

“My children are dead,” said my foster father quietly. “I’ve accepted that. I wouldn’t expect her or anyone else to replace them.”

The doctor was silent for a moment. Then he sighed. “Well, at least she can talk.”

“Of course she can talk! She is human, Bart, wild or not.”

“Yes…physically anyway. Some of them can’t do much more than grunt, you know. They’ve either forgotten speech, or they never learned it. As wild humans, they spend their lives either hunting or being hunted. By the time they’re this girl’s age, they’re more wild than human.”

“This one’s a future Missionary,” said my foster father. “She’ll learn. She’ll become one of us.”

“Maybe.” The doctor sounded doubtful. “If the people let her, and if she really wants to. But I think all she’ll learn for quite a while is how to pretend to be one of us. Don’t expect more than that.”

And my foster father didn’t at first. I don’t think he had even before the doctor warned him. All he asked of me was that I learn to put on a good act when I was with people other than him and his wife Neila. That would protect me from the less tolerant of his Missionaries. Perhaps during that early period, he was too tolerant himself, though, too willing to let me stand apart from his people as I was naturally inclined to do. Perhaps there was a time when I could have become a Missionary if he had insisted, pushed me. But as it happened, it was best for him, for his people, and especially for me, that he did not insist. Best that when we left Earth and settled on our new world, I became something else entirely.

Two days after Alanna Verrick was rescued from her Tehkohn captors, the sharp edge of her pain began to wear away. She could think again. She could look at her situation clearly and realize how much trouble she was in.

Her rescuers, complacent and overconfident after their victorious raid, were also in trouble but they did not know it. In fact, their ignorance was one of Alanna’s problems. But she had another more immediate problem. In a very short time, she was going to have to convince her rescuers that they had not made a mistake in setting her free.

For now, though, she followed them silently as she had for the past two days while they herded their own Tehkohn prisoners down from the mountains. They had already reached the foothills and Alanna could look down from the trail into the valley’s thick covering of yellow-green meklah trees. For the first time in nearly eight hundred days—two local years—she saw the planet’s only settlement of Earth humans. The Mission colony that had once been her home. Like her, it had changed.

The Missionaries had transformed their settlement from a scattered collection of cabins almost hidden by the surrounding trees to a solidly stockaded town—a fortress that apparently provided them with the dangerous illusion of security.

Alanna looked around for some sign of the Garkohn town. Since the Garkohn, native allies of the Missionaries, chose to live underground, a sign of their town would be a small hill somewhere along the eastern side of the valley—the far side. But there were many such hills, all natural-looking, all identically covered with meklah trees and shrubs. The Garkohn knew that real security began with adequate camouflage. But then, the Missionaries considered this world’s version of even adequate camouflage to be beyond their reach. The expertise of the natives intimidated them.

Thus, only the Missionary fortress stood in plain view, beckoning unwittingly to the Tehkohn—inviting them to steal in and butcher everyone without even the inconvenience of a battle. And, Alanna guessed, after the defeat that the Tehkohn had just suffered, they would be strongly motivated to do just that.

Alanna looked back at the Tehkohn prisoners. They walked together in a group completely surrounded by their Garkohn and Missionary captors. She noticed that one of the prisoners, the big blue one, was watching her. This startled her because until now, he had been very careful to pay no attention to her at all. She turned away quickly.

Her foster father, Jules Verrick, was walking beside her. He noticed the gesture and naturally misinterpreted it.

“Don’t worry,” he said. “They’re well guarded. For once, they’re the prisoners instead of us.”

Silently, Alanna found fault with the inclusive “us.” She alone had been a prisoner of the Tehkohn. Others, Garkohn and Missionary, had been captured with her, but they were dead. Only Alanna had managed to live beyond the first few days of her captivity. Only she had survived to be rescued.

Jules spoke again gently. “You’ll feel better when we get home and those creatures are locked up out of your sight.”

She nodded meaninglessly, wondering whether he really thought that after two years among the Tehkohn, she could still be upset by the sight of them. She looked out over the valley again. The sight of the defenseless Missionary fortress had far more power to upset her. In the long run, the Missionaries were in greater danger than she was.

She glanced at the prisoners again, seeing them in a different way now—seeing them as living shields for the Missionaries.

“How many of the prisoners are yours, Jules?” she asked. He was the Missionary leader and would know exactly.

“Five hunters,” he answered, “and one of the blue-green types.”

“A judge,” said Alanna. “Higher than a hunter among the Tehkohn.”

“Yes, and…all the farmers are ours.” He sounded a little ashamed of this last. As far as Alanna was concerned, he had reason to be. Farmers and artisans were nonfighters. Capturing them was no achievement. The Garkohn had taken none of them. The Garkohn had hunters, judges, and one other. These were the prisoners who would have been most useful to the Missionaries. Prisoners whom the Tehkohn could ill afford to lose, prisoners whom the Missionaries could shield themselves behind and negotiate through. The Missionaries could negotiate a peace now that all Tehkohn would respect if Jules could only speak privately with the prisoners who belonged to the Garkohn. Such a peace had to be arranged if the Missionaries were to survive. And Alanna had to arrange it somehow. That was the responsibility she had assigned herself. It was not a responsibility she wanted. It would center the attention of three warring peoples on her. If she made a mistake, on

e of the groups would surely kill her. But she was the only person with the knowledge, and possibly the leverage, to manage it. And she owed her foster parents a debt. Years before, they had saved her. Now she would try to save them, and save their Mission, which meant so much to them. She had to try.

“Lanna?”

Alanna looked at her foster father knowing from his apologetic tone that she would probably not like what he had to say.

“Natahk has been wanting to talk to you—ask you a few questions about your stay with the Tehkohn.”

Alanna turned away from him, striving to conceal her fear and anger. Here was the personal trouble she had been anticipating. Natahk was the Garkohn leader, their First Hunter. She could show fear at having to see him, but she had to be careful not to show her anger. “I guess I should have expected that,” she said.

Jules put an arm around her. “Look,” he said, “I know how you must feel about the natives—any natives—after what you’ve been through. If you think talking to Natahk will be too much for you right now, I’ll tell him you can’t…”

“No,” she said. “It’s all right, Jules. I’ll see him.”

He looked at her with concern. “You’re frightened,” he said, “and sick. You’ve been like a sleepwalker these past two days. I shouldn’t have bothered you with this. I’m going to tell him to wait.”

Tempted to let him go ahead, she kept silent for a long moment. She did not want to talk to anyone about her experiences with the Tehkohn, did not want to talk to a Garkohn about anything at all. She had no doubt that the Garkohn were responsible for involving the Missionaries in this raid that had so endangered them—just as two years before, the Garkohn had made the Missionaries vulnerable by using their settlement as a base from which to raid the Tehkohn. The valley natives were not the friends the Missionaries thought them to be. Alanna had learned much about them from their Tehkohn enemies. And she had seen some of what she had learned proven in the raid just past.

The thought of having to go to Natahk now and feign ignorance and friendship sickened her. But for that reason more than any other, she had to do it. She had to let him ask her in carefully veiled words where her loyalties were. What had two years among his enemies done to her? Had he freed a Missionary prisoner, or a Tehkohn spy?

“I’m well enough, Jules,” she said finally. “I’ll talk to him.”

Jules shrugged. “All right, girl. It’s your decision.”

After perhaps another hour of walking, Jules and Natahk called the noon rest stop. Alanna sought out Natahk at once.

The Garkohn leader was a tall stocky humanoid who easily matched Alanna’s own unusual height—nearly two meters. His height and his deeper-than-usual green coloring showed that although he was of the hunter clan, he had had a judge ancestor or two. It was only within Natahk’s own lifetime that the last of the Garkohn judges had been killed, victims of interclan fighting with the more numerous hunters.

Natahk’s eyes were narrowed by a Kohn version of the epicanthic fold. His fur grew longer and thicker on his head and around his neck and shoulders, forming a kind of mane. Even his face was furred all over, though the fur was shorter. But the face was long and flat and his body and limbs were humanly proportioned. He was not apelike. The Missionaries saw him and his people as strangely colored, furred caricatures of human beings.

The Missionaries had made a religion of maintaining and spreading their own version of humanity—a religion that had helped them to preserve that humanity back on Earth. Now, though, their religion had gotten in their way. It had helped them to justify their belief that the Kohn were lower creatures—higher than apes, but lower than true humans who had been made in the image of God. The trouble was, the Missionaries had known such “intelligent animals” before. Missionary prejudices were long established and, as far as Alanna was concerned, dangerous. If she had accepted them herself, the Tehkohn would have rid her of them. The natives were human enough. And they were powerful humans.

Their greatest weapon was the fur that the Missionaries condemned them for. It was unlike any fur that the Missionaries had known back on Earth—fine thick alive stuff that changed color and seemed to change texture. It permitted the natives to blend invisibly into their surroundings whenever they wished. It could permit the Tehkohn to camouflage themselves as they scaled the Missionaries’ wall. It could permit them to murder half the colony before anyone noticed them.

Alanna found Natahk seated on the ground, his back against a tree. She noticed that he had moved as far from the Tehkohn prisoners as he could get without leaving the group entirely. Many of the prisoners were bluer than he was and would have outranked him had they been Garkohn. As the bluest of the Garkohn, he must have felt that they detracted from his impressiveness. And they did, even in Alanna’s eyes. She smiled at the thought of his discomfort as she approached him.

“Natahk,” she greeted quietly as she sat down opposite him.

He startled her by drawing his lipless mouth into a smile. “Alanna.” It was something he had copied from the Missionaries, not a Kohn expression. And he did it badly. He made it an expression of condescension, of contempt, rather than one of friendliness.

“Jules said you had questions.” Alanna concentrated on speaking English. She did not attempt to speak Garkohn, knowing how easy it would be for her to offend Natahk by slipping into the more familiar Tehkohn dialect.

“I have several questions,” said Natahk. “But first, I want to tell you that I know of your loss, and that I’m sorry.”

Alanna froze, stared at him in disbelief. Suddenly, she was fighting to maintain her self-control. But the wound the Garkohn had prodded was too raw, too new. How could he know? How could he?

Natahk went on. “We tried hard to prevent your daughter’s death. I’m sorry we failed.”

Alanna felt her control cracking, falling away. Abruptly, she folded forward and down as though in physical pain so that her face was hidden by the black veil of her hair. She made no sound. Her grief was not something to share with the Garkohn liar, the Garkohn murderer! What tricks had he used to make Jules join him in raiding the Tehkohn—join him indirectly in the murder of her child?

Still silent, unmoving, Alanna decided that Natahk would die. No matter what else happened, no matter what other revenge the Tehkohn managed to take, this Garkohn would die.

She held her position of distress several seconds longer than necessary so that when she rose, the last signs of anguish were gone from her face. Replacing them was cold hatred.

“We did not kill your child,” said Natahk. “You know that.”

She said nothing, wondered again how Natahk could possibly have known that one of the children killed in the raid had been hers. As though to draw away from its pain, her mind worried at the question.

Her daughter Tien had not been the bright golden-green of most Kohn infants. But the child’s darker strangely shaded green was not beyond the Kohn spectrum—especially not beyond the Tehkohn spectrum. It might have meant no more than that Tien was destined for higher rank than the children who had more yellow in their coloring. And Tien had looked Tehkohn—almost. Her eyes were rounder than Kohn eyes, and her hands and feet promised to be too large, too long for a Kohn. Small things, especially in such a young child. Natahk’s people would almost have had to be looking for such a child. And even having found Tien, they could not have been sure. Natahk could not have been sure…

Alanna looked at him with Tehkohn-trained eyes. At once, she detected the slight brightening of his coloring—lighter toward white. That was the only sign he gave of his triumph, his success at tricking her into confirming his suspicions. And he was not used to Missionaries reading such small signs. He seemed to think he was still adequately maintaining his facade of solemnity and concern. He had tricked her so easily. Now he sat waiting to do it again.

“Do you know how my daughter died?” she asked. She kept her voice low and calm.

“I was told that a T

ehkohn huntress killed her to keep her from being taken by my hunters.”

“So.” She switched abruptly to Tehkohn, allowing her anger to show. It made no difference now. The Garkohn was already well aware of which side she had to be on. “One of your hunters fed her from his bag of meklah poison while several Tehkohn were forced to watch. He did it so that he could enjoy their reactions; I was there. It is only because the Tehkohn broke ranks so quickly to tear him apart that your hunters had no time to notice my reaction. By the time your hunters had killed some of the Tehkohn and restored order, a Tehkohn huntress had killed my child.” Alanna stared at him in silence for a moment, then continued bitterly. “Do you know that I understand what she did, First Hunter? Do you know that I am grateful to her for saving my child from the life that meklah addiction would have condemned her to—the life of a Garkohn!” She made the name an obscenity.

But she was lying. Tien’s life meant more to her than any tribal feud, more than any personal prejudice. She would rather have had her daughter alive even addicted to meklah, and thus confined to the valley. But Natahk did not know that. He would believe her, and he would know that he could never again use Tien’s death as a tool to pry information from her. That was all Alanna wanted.

She started to rise to leave him and he caught her arm in a thick, powerful, short-fingered hand. His grip was loose, however, only warning.

“I’m not finished, Alanna.”

She looked at his hand, then at him. “The Missionaries may not be able to hear us at this distance, Natahk, but they can see us well enough.”

He released her arm and again she started to leave.

“Sit still!”

She was stopped by his tone rather than his words. She looked at him and saw that his coloring had taken on more yellow with his anger. He spoke again.

“You will talk to me now, or I will have my hunters take you from the Mission settlement and bring you to me later.”

Slowly, stunned, she sat back down. He meant it. She was alerted now; he would not deceive her again. But he had already goaded her into admitting that she was his enemy, and he would treat her as an enemy. He knew the Missionaries well enough to realize that she could not afford to have them learn that she had accepted a Tehkohn man, borne a “subhuman” child. Exodus 22:19: “Whosoever lieth with a beast shall surely be put to death.” Such a sin could turn even Jules and Neila Verrick against her. Thus, Natahk felt free to threaten her, and to carry out his threat if she made it necessary. She would be in no position to complain.

Patternmaster

Patternmaster Survivor

Survivor Clay's Ark

Clay's Ark Bloodchild and Other Stories

Bloodchild and Other Stories Parable of the Sower

Parable of the Sower Wild Seed

Wild Seed Fledgling

Fledgling Unexpected Stories

Unexpected Stories Kindred

Kindred Lilith's Brood: Dawn / Adulthood Rites / Imago

Lilith's Brood: Dawn / Adulthood Rites / Imago Adulthood Rites

Adulthood Rites Mind of My Mind

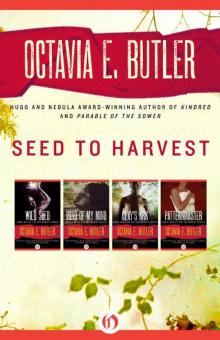

Mind of My Mind Seed to Harvest

Seed to Harvest Lilith's Brood: Dawn, Adulthood Rites, and Imago (Xenogenesis Trilogy)

Lilith's Brood: Dawn, Adulthood Rites, and Imago (Xenogenesis Trilogy) Bloodchild

Bloodchild Seed to Harvest: Wild Seed, Mind of My Mind, Clay's Ark, and Patternmaster (Patternist)

Seed to Harvest: Wild Seed, Mind of My Mind, Clay's Ark, and Patternmaster (Patternist)