- Home

- Octavia E. Butler

Lilith's Brood: Dawn, Adulthood Rites, and Imago (Xenogenesis Trilogy) Page 12

Lilith's Brood: Dawn, Adulthood Rites, and Imago (Xenogenesis Trilogy) Read online

Page 12

Nikanj had taken her, on the day before it put her into this huge, empty room, down several corridors and ramps, then by way of something very like an elevator. Nikanj said it corresponded closer to a gas bubble moving harmlessly through a living body. Her destination turned out to be a kind of observation bubble through which she could see not only stars, but the disk of the Earth, gleaming like a full moon in the black sky.

“We’re still beyond the orbit of your world’s satellite,” it told her as she searched hungrily for familiar continental outlines. She believed she had found a few of them—part of Africa and the Arabian peninsula. Or that was what it looked like, hanging there in the middle of a sky that was both above and beneath her feet. There were more stars out there than she had ever seen, but it was Earth that drew her gaze. Nikanj let her look at it until her own tears blinded her. Then it wrapped a sensory arm around her and led her to the great room.

She had been in the great room alone for three days now, thinking, reading, writing her thoughts. All her books, papers, and pens had been left for her. With them were eighty dossiers—short biographies made up of transcribed conversations, brief histories, Oankali observations and conclusions, and pictures. The human subjects of the dossiers had no living relatives. They were all strangers to one another and to Lilith.

She had read just over half the dossiers, searching not only for likely people to Awaken, but for a few potential allies—people she could Awaken first and perhaps come to trust. She needed to share the burden of what she knew, what she must do. She needed thoughtful people who would hear what she had to say and not do anything violent or stupid. She needed people who could give her ideas, push her mind in directions she might otherwise miss. She needed people who could tell her when they thought she was being a fool—people whose arguments she could respect.

On another level, she did not want to Awaken anyone. She was afraid of these people, and afraid for them. There were so many unknowns, in spite of the information in the dossiers. Her job was to weave them into a cohesive unit and prepare them for the Oankali—prepare them to be the Oankali’s new trade partners. That was impossible.

How could she Awaken people and tell them they were to be part of the genetic engineering scheme of a species so alien that the humans would not be able to look at it comfortably for a while? How would she Awaken these people, these survivors of war, and tell them that unless they could escape the Oankali, their children would not be human?

Better to tell them little or none of that for a while. Better not to Awaken them at all until she had some idea how to help them, how not to betray them, how to get them to accept their captivity, accept the Oankali, accept anything until they were sent to Earth. Then to run like hell at the first opportunity.

Her mind slipped into the familiar track: There was no escape from the ship. None at all. The Oankali controlled the ship with their own body chemistry. There were no controls that could be memorized or subverted. Even the shuttles that traveled between Earth and the ship were like extensions of Oankali bodies.

No human could do anything aboard the ship except make trouble and be put back into suspended animation—or be killed. Therefore, the only hope was Earth. Once they were on Earth—somewhere in the Amazon basin, she had been told—they would at least have a chance.

That meant they must control themselves, learn all she could teach them, all the Oankali could teach them, then use what they had learned to escape and keep themselves alive.

What if she could make them understand that? And what if it turned out that that was exactly what the Oankali wanted her to do? Of course, they knew it was what she would do. They knew her. Did that mean they were planning their own betrayal: No trip to Earth. No chance to run. Then why had they made her spend a year being taught to live in a tropical forest? Perhaps the Oankali were simply very certain of their ability to keep humans corralled even on Earth.

What could she do? What could she tell the humans but “Learn and Run!” What other possibility for escape was there?

None at all. Her only other personal possibility was to refuse to Awaken anyone—hold out until the Oankali gave up on her and went looking for a more cooperative subject. Another Paul Titus, perhaps—someone who had truly given up on humanity and cast his lot with the Oankali. A man like that could make Titus’ predictions self-fulfilling. He could undermine what little civilization might be left in the minds of those he Awoke. He could make them a gang. Or a herd.

What would she make them?

She lay on her bed platform, staring at a picture of a man. Five-seven, his statistics said. One hundred and forty pounds, thirty-two years old, missing the third, fourth, and fifth fingers of his left hand. He had lost the fingers in a childhood accident with a lawn mower, and he was self-conscious about the incomplete hand. His name was Victor Dominic—Vidor Domonkos, really. His parents had come to the United States from Hungary just before he was born. He had been a lawyer. The Oankali suspected he had been a good one. They had found him intelligent, talkative, understandably suspicious of unseen questioners, and very creative at lying to them. He had probed constantly for their identity, but was, like Lilith, one of the few native English-speakers who had never expressed the suspicion that they might be extraterrestrials.

He had been married three times already, but had fathered no children due to a biological problem the Oankali believed they had corrected. Not fathering children had bothered him intensely, and he had blamed his wives, all the while refusing to see a doctor himself.

Apart from this, the Oankali had found him reasonable and formidable. He had never broken down in his unexplained solitary confinement, had never wept or attempted suicide. He had, however, promised to kill his captors if he ever got the chance. He had said this only once, calmly, more as though he were making a casual remark than as though he were seriously threatening murder.

Yet his Oankali interrogator had been disturbed by the words, and had put Victor Dominic back to sleep at once.

Lilith liked the man. He had brains and, except for the foolishness with his wives, self-control—exactly what she needed. But she also feared him.

What if he decided she was one of his captors? She was bigger, and now certainly stronger than he was, but that did not have to matter. He would have too many chances to attack when she was off guard.

Better to Awaken him later when she had allies. She put his dossier to one side on the smaller of two piles—people she definitely wanted, but did not dare to Awaken first. She sighed and picked up a new dossier.

Leah Bede. Quiet, religious, slow—slow-moving, not slow-witted, though the Oankali had not been particularly impressed by her intelligence. It was her patience and self-sufficiency that had impressed them. They had not been able to make her obey. She had outwaited them in stolid silence. Outwaited Oankali! She had starved herself almost to death when they stopped feeding her to coerce her cooperation. Finally, they had drugged her, gotten the information they wanted, and, after a period of letting her regain weight and strength, they had put her back to sleep. Why, Lilith wondered. Why hadn’t the Oankali not simply drugged her as soon as they realized she was stubborn? Why had they not drugged Lilith herself? Perhaps because they wanted to see how far human beings had to be pushed before they broke. Perhaps they even wanted to see how each individual broke. Or perhaps the Oankali version of stubbornness was so extreme from a human point of view that very few humans tried their patience. Lilith had not. Leah had.

The photo of Leah was a pale, lean, tired-looking woman, though an ooloi had noted that she had a physiological tendency to be heavy.

Lilith hesitated, then put Leah’s folder atop Victor’s. Leah, too, sounded like a good potential ally, but not a good one to Awaken first. She sounded as though she could be an intensely loyal friend—unless she got the idea Lilith was one of her captors.

Anyone Lilith Awakened might get that idea—almost certainly would get it the moment Lilith opened a wall or caused

new walls to grow, thus proving she had abilities they did not. The Oankali had given her information, increased physical strength, enhanced memory, and an ability to control the walls and the suspended animation plants. These were her tools. And every one of them would make her seem less human.

“What else shall we give you?” Ahajas had asked her when Lilith saw her last. Ahajas had worried about her, found her too small to be impressive. She had discovered that humans were impressed by size. The fact that Lilith was taller and heavier than most women seemed not enough. She was not taller and heavier than most men. But there was nothing to be done about it.

“Nothing you could give me would be enough,” Lilith had answered.

Dichaan had heard this and come over to take Lilith’s hands. “You want to live,” he told her. “You won’t squander your life.”

They were squandering her life.

She picked up the next folder and opened it.

Joseph Li-Chin Shing. A widower whose wife had died before the war. The Oankali had found him quietly grateful for that. After his own period of stubborn silence, he had discovered that he didn’t mind talking to them. He seemed to accept the reality that his life was, as he said, “on hold” until he found out what had happened in the world and who was running things now. He constantly probed for answers to these questions. He admitted that he remembered deciding, not long after the war, that it was time for him to die. He believed that he had been captured before he could attempt suicide. Now, he said, he had reason to live—to see who had caged him and why and how he might want to repay them.

He was forty years old, a small man, once an engineer, a citizen of Canada, born in Hong Kong. The Oankali had considered making him a parent of one of the human groups they meant to establish. But they had been put off by his threat. It was, the Oankali questioner thought, soft, but potentially quite deadly. Yet the Oankali recommended him to her—to any first parent. He was intelligent, they said, and steady. Someone who could be depended on.

Nothing special about his looks, Lilith thought. He was a small, ordinary man, yet the Oankali had been very interested in him. And the threat he had made was surprisingly conservative—deadly only if Joseph did not like what he found out. He would not like it, Lilith thought. But he would also be bright enough to realize that the time to do something about it would be when they were all on the ground, not while they were caged in the ship.

Lilith’s first impulse was to Awaken Joseph Shing—Awaken him at once and end her solitude. The impulse was so strong that she sat still for several moments, hugging herself, holding herself rigid against it. She had promised herself that she would not Awaken anyone until she had read all the dossiers, until she had had time to think. Following the wrong impulse now could kill her.

She went through several more dossiers without finding anyone she thought compared with Joseph, though some of the people she found would definitely be Awakened.

There was a woman named Celene Ivers who had spent much of her short interrogation period crying over the death of her husband and her twin daughters, or crying over her own unexplained captivity and her uncertain future. She had wished herself dead over and over, but had never made any attempt at suicide. The Oankali had found her very pliable, eager to please—or rather, fearful of displeasing. Weak, the Oankali had said. Weak and sorrowing, not stupid, but so easily frightened that she could be induced to behave stupidly.

Harmless, Lilith thought. One person who would not be a threat, no matter how strongly she suspected Lilith of being her jailer.

There was Gabriel Rinaldi, an actor, who had confused the Oankali utterly for a while because he played roles for them instead of letting them see him as he was. He was another they had finally stopped feeding on the theory that sooner or later hunger would bring out the true man. They were not entirely sure that it had. Gabriel must have been good. He was also very good-looking. He had never tried to harm himself or threatened to harm the Oankali. And for some reason, they had never drugged him. He was, the Oankali said, twenty-seven, thin, physically stronger than he looked, stubborn and not as bright as he liked to think.

That last, Lilith thought, could be said of most people. Gabriel, like the others who had defeated or come near defeating the Oankali, was potentially valuable. She did wonder whether she would ever be able to trust Gabriel, but his dossier remained with those she meant to Awaken.

There was Beatrice Dwyer who had been completely unreachable while she was naked, but whom clothing had transformed into a bright, likable person who seemed actually to have made a friend of her interrogator. That interrogator, an experienced ooloi, had attempted to have Beatrice accepted as a first parent. Other interrogators had observed her and disagreed for no stated reason. Maybe it was just the woman’s extreme physical modesty. Nevertheless, one ooloi had been completely won over.

There was Hilary Ballard, poet, artist, playwright, actress, singer, frequent collector of unemployment compensation. She really was bright; she had memorized poetry, plays, songs—her own and those of more established writers. She had something that would help future human children remember who they were. The Oankali thought she was unstable, but not dangerously so. They had had to drug her because she injured herself trying to break free of what she called her cage. She had broken both her arms.

And that was not dangerously unstable?

No, it probably was not. Lilith herself had panicked at being caged. So had a great many other people. Hilary’s panic had simply been more extreme than most. She probably should not be given crucial work to do. The survival of the group should never depend on her—but then it should not depend on any one person. The fact that it did was not the fault of human beings.

There was Conrad Loehr—called Curt—who had been a cop in New York, and who had survived only because his wife had finally dragged him off to Colombia where her family lived. They had not gone anywhere for years before that. The wife had been killed in one of the riots that began shortly after the last missile exchange. Thousands had been killed even before it began to get cold. Thousands had simply trampled one another or torn one another apart in panic. Curt had been picked up with seven children, none of them his own, whom he had been guarding. His own four children, left back in the States with his relatives, were all dead. Curt Loehr, the Oankali said, needed people to look after. People stabilized him, gave him purpose. Without them, he might have been a criminal—or dead. He had, alone in his isolation room, done his best to tear out his own throat with his fingernails.

Derick Wolski had been working in Australia. He was single, twenty-three, had no strong idea what he wanted to do with his life, had done nothing so far except go to school and work at temporary or part-time jobs. He’d fried hamburgers, driven a delivery truck, done construction work, sold household products door to door—badly—bagged groceries, helped clean office buildings, and on his own, done some nature photography. He’d quit everything except the photography. He liked the outdoors, liked animals. His father thought that sort of thing was nonsense, and he had been afraid his father might be right. Yet, he had been photographing Australian wildlife when the war began.

Tate Marah had just quit another job. She had some genetic problem that the Oankali had controlled, but not cured. But her real problem seemed to be that she did things so well that she quickly became bored. Or she did them so badly that she abandoned them before anyone noticed her incompetence. People had to see her as a formidable presence, bright, dominant, well off.

Her family had had money—had owned a very successful real estate business. Part of her problem, the Oankali believed, was that she did not have to do anything. She had great energy, but needed some external pressure, some challenge to force her to focus it.

How about the preservation of the human species?

She had attempted suicide twice before the war. After the war, she fought to live. She had been alone, vacationing in Rio de Janeiro when war came. It had not been a good time to be a

North American, she felt, but she had survived and managed to help others. She had that in common with Curt Loehr. Under Oankali interrogation, she had engaged in verbal fencing and game playing that eventually exasperated the ooloi questioner. But in the end, the ooloi had admired her. It thought she was more like an ooloi than like a female. She was good at manipulating people—could do it in ways they did not seem to mind. That had bored her too in the past. But boredom had not driven her to do harm to anyone except herself. There had been times when she withdrew from people to protect them from the possible consequences of her own frustration. She had withdrawn from several men this way, occasionally pairing them off with female friends. Couples she brought together tended to marry.

Lilith put Tate Marah’s dossier down slowly, left it by itself on the bed. The only other one that was by itself was Joseph Shing’s. Tate’s dossier fell open, once again displaying the woman’s small, pale, deceptively childlike face. The face was smiling slightly, not as though posing for a picture, but as though sizing up the photographer. In fact, Tate had not known the picture was being made. And the pictures were not photographs. They were paintings, impressions of the inner person as well as the outer physical reality. Each contained print memories of their subjects. Oankali interrogators had painted these pictures with sensory tentacles or sensory arms, using deliberately produced bodily fluids. Lilith knew this, but the pictures looked like, even felt like photos. They had been done on some kind of plastic, not on paper. The pictures looked alive enough to speak. In each one, there was nothing except the head and shoulders of the subject against a gray background. None of them had that blank, wanted-poster look that snapshots could have produced. These pictures had a lot to say even to non-Oankali observers about who their subjects were—or who the Oankali thought they were.

Tate Marah, they thought, was bright, somewhat flexible, and not dangerous except perhaps to the ego.

Lilith left the dossiers, left her private cubicle, and began building another near it.

Patternmaster

Patternmaster Survivor

Survivor Clay's Ark

Clay's Ark Bloodchild and Other Stories

Bloodchild and Other Stories Parable of the Sower

Parable of the Sower Wild Seed

Wild Seed Fledgling

Fledgling Unexpected Stories

Unexpected Stories Kindred

Kindred Lilith's Brood: Dawn / Adulthood Rites / Imago

Lilith's Brood: Dawn / Adulthood Rites / Imago Adulthood Rites

Adulthood Rites Mind of My Mind

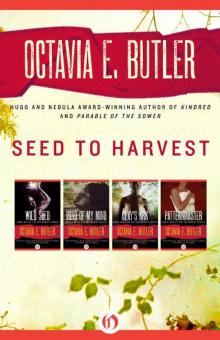

Mind of My Mind Seed to Harvest

Seed to Harvest Lilith's Brood: Dawn, Adulthood Rites, and Imago (Xenogenesis Trilogy)

Lilith's Brood: Dawn, Adulthood Rites, and Imago (Xenogenesis Trilogy) Bloodchild

Bloodchild Seed to Harvest: Wild Seed, Mind of My Mind, Clay's Ark, and Patternmaster (Patternist)

Seed to Harvest: Wild Seed, Mind of My Mind, Clay's Ark, and Patternmaster (Patternist)