- Home

- Octavia E. Butler

Parable of the Sower Page 12

Parable of the Sower Read online

Page 12

She put down her own real fruit picker with its awkward extension handle and small fruit-catching basket. It was best for persimmons. She hugged herself. “I’ve lived here, lived with trees and gardens all my life. I…don’t know how it will be to be shut up in an apartment. It does scare me, but we’ll manage. We’ll have to.”

“You can come back here if things aren’t what you hope. Your grandparents and your aunt’s family will still be here.”

“Harry will still be here,” she whispered, looking toward her house. I would have to stop thinking of it as the Garfield house. Harry and Joanne were at least as close as Curtis and I. I hadn’t thought about her leaving him—what that must be like. I like Harry Baiter. I remember being surprised when he and Joanne first started going together. They’d lived in the same house all their lives. I had thought of Harry almost as her brother. But they were only first cousins, and against the odds, they had managed to fall in love. Or I thought they had. They hadn’t gone with anyone else for years. Everyone assumed they would get around to marrying when they were a little older.

“Marry him and take him with you,” I said.

“He won’t go,” she said in that same whisper. “We’ve talked and talked about it. He wants me to stay here with him, get married soon and go north. Just…go with no prospects. Nothing. It’s crazy.”

“Why won’t he go to Olivar?”

“He thinks the way your father does. He thinks Olivar’s a trap. He’s read about nineteenth and early twentieth century company towns, and he says no matter how great Olivar looks, all we’ll get from it in the end is debt and loss of freedom.”

I knew Harry had sense. “Jo,” I said, “you’ll be of age next year. You could stay here with the Baiters until then and marry. Or you could talk your father into letting you marry now.”

“And then what? Go join the street poor? Stay and stuff more babies into that crowded house. Harry doesn’t have a job, and there’s no real chance of his getting one that pays money. Are we supposed to live on what Harry’s parents earn? What kind of future is that? None! None at all!”

Sensible. Conservative and sensible and mature and wrong. Very much in character with Joanne.

Or maybe I was the one who was wrong. Maybe the security Joanne will find in Olivar is the only kind of security to be had for anyone who isn’t rich. To me, though, security in Olivar isn’t much more attractive than the security Keith has finally found in his urn.

I picked a few more lemons and some oranges and wondered what she would do if she knew I was also planning to leave next year. Would she run to her mother again, frightened for me, and eager to have someone protect me from myself? She might. She wants a future she can understand and depend on—a future that looks a lot like her parents’ present. I don’t think that’s possible. Things are changing too much, too fast. Who can fight God?

We put baskets of fruit inside my back door on the porch, then headed for her house.

“What will you do?” she asked me as we walked. “Are you just going to stay here? I mean…are you going to stay and marry Curtis?”

I shrugged and lied. “I don’t know. If I marry anyone, it will be Curtis. But I don’t know about marrying. I don’t want to have children here any more than you do. I know we’ll be staying here for a while longer, though. Dad won’t let Cory even apply to Olivar. I’m glad of that because I don’t want to go there. But there’ll be other Olivars. Who knows what I might wind up doing?” That last didn’t feel like a lie.

“You think there’ll be more privatized cities?” she asked.

“Bound to be if Olivar succeeds. This country is going to be parceled out as a source of cheap labor and cheap land. When people like those in Olivar beg to sell themselves, our surviving cities are bound to wind up the economic colonies of whoever can afford to buy them.”

“Oh, God, there you go again. You’ve always got a disaster up your sleeve.”

“I see what’s out there. You see it too. You just deny it.”

“Remember when you thought starving hordes were going to come crawling over our walls and we would have to run away to the mountains and eat grass?”

Did I remember? I turned to face her, first angry—furious—then to my own surprise, sad. “I’ll miss you,” I said.

She must have read my feelings. “I’m sorry,” she whispered.

We hugged each other. I didn’t ask her what she was sorry for, and she didn’t say any more.

TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 17, 2026

Dad didn’t come home today. He was due this morning.

I don’t know what that means. I don’t know what to think. I’m scared to death.

Cory called the college, his friends, fellow ministers, co-workers, the cops, the hospitals…

Nothing. He isn’t under arrest or sick or injured or dead—at least not as far as anyone knows. None of his friends or colleagues had seen him since he left work early this morning. His bike was working all right. He was all right.

He had ridden off toward home with three co-workers who lived in other neighborhoods in our area. Each of these said the same thing: That they had left him as usual at River Street where it intersects Durant Road. That’s only five blocks from here. We’re at the tip-end of Durant Road.

So where is he?

Today a group of us, all armed, rode bicycles from home to River Street and down River Street to the college. Five miles in all. We checked side streets, alleys, vacant buildings, every place we could think of. I went. I took Marcus with me because if I hadn’t, he would have gone out alone. I had the Smith & Wesson. Marcus had only his knife. He’s quick and agile with it, and strong for his age, but he’s never used it on anything alive. If anything had happened to him, I don’t think I would have dared to go home. Cory is already out of her mind with worry. All this on top of losing Keith… I don’t know. Everyone helped. Jay Garfield will be leaving soon, but that didn’t stop him from leading the search. He’s a good man. He did everything he could think of to find Dad.

Tomorrow we’re going into the hills and canyons. We have to. No one wants to, but what else can we do?

WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 18, 2026

I’ve never seen more squalor, more human remains, more feral dogs than I saw today. I have to write. I have to dump this onto paper. I can’t keep it inside of me. Seeing the dead has never bothered me before, but this…

We were looking for Dad’s body, of course, though no one said so. I couldn’t deny that reality or avoid thinking about it. Cory checked with the police again, with the hospitals, with everyone we could think of who knew Dad.

Nothing.

So we had to go to the hills. When we go for target practice, we don’t look around, except to ensure safety. We don’t look for what we’d rather not find. Today in groups of three or four, we combed through the area nearest to the top of River Street. I kept Marcus with me—which was not easy. What is it in young boys that makes them want to wander off alone and get killed? They get two chin hairs and they’re trying to prove they’re men.

“You watch my back and I’ll watch yours,” I said. “I’m not going to let you get hurt. Don’t you let me down.”

He gave me the kind of near-smile that said he knew exactly what I was trying to do, and that he was going to do as he pleased. I got mad and grabbed him by the shoulders.

“Dammit, Marcus, how many sisters have you got? How many fathers have you got!” I never used even mild profanity with him unless things were very serious. Now, it got his attention.

“Don’t worry,” he muttered. “I’ll help.”

Then we found the arm. Marcus was the one who spotted it—something dark lying just off the trail we were following. It was hung up in the low branches of a scrub oak.

The arm was fresh and whole—a hand, a lower, and an upper arm. A black man’s arm, just the color of my father’s where color could be seen. It was slashed and cut all over, yet still powerful looking—long-boned, long-fingered, yet m

uscular and massive… Familiar?

Smooth, white bone stuck out at the shoulder end. The arm had been cut off with a sharp knife. The bone wasn’t broken. And, yes. It could have been his.

Marcus threw up when he saw it. I made myself examine it, search it for something familiar, for certainty. Jay Garfield tried to stop me, and I shoved him away and told him to go to hell. I’m sorry for that, and I told him so later. But I had to know. And yet, I still don’t know. The arm was too slashed and covered in dried blood. I couldn’t tell. Jay Garfield took fingerprints in his pocket notebook, but we left the arm itself. How could we take that back to Cory?

And we kept searching. What else could we do? George Hsu found a rattlesnake. It didn’t bite anyone and we didn’t kill it. I don’t think anyone was in a mood to kill things.

We saw dogs, but they kept away from us. I even saw a cat watching us from under a bush. Cats either run like hell or crouch and freeze. They’re interesting to watch, somehow. Or, at any other time, they’d be interesting.

Then someone began to scream. I’ve never heard screams like that before—on and on. A man, screaming, begging, praying: “No! No more! Oh, God, no more, please. Jesus, Jesus, Jesus, please!” Then there were wordless, grating cries and high, horrible mewling.

It was a man’s voice, not like my father’s but not that different from his. We couldn’t locate the source. The echoes bounced around the canyon, confusing us, sending us first in one direction, then in another. The canyon was full of loose rock and spiny, vicious plants that kept us on the pathways where there were pathways.

The screaming stopped, then began again as a kind of horrible, bubbling noise.

I had let myself fall back to the end of the line of us by then. I wasn’t in trouble. Sound doesn’t trigger my sharing. I have to see another person in pain before I do any sharing. And this was one I’d do anything to avoid seeing.

Marcus dropped back beside me and whispered, “You okay?”

“Yeah,” I said. “I just don’t want to know anything about what’s happening to that man.”

“Keith,” he said.

“I know,” I agreed.

We walked our bikes behind the others, watching the back trail. Kayla Talcott dropped back to see if we were all right. She hadn’t wanted us to come, but since we had come, she had come, she had kept an eye on us. She’s like that.

“It doesn’t sound like your daddy,” she said. “Doesn’t sound like him at all.” Kayla is from Texas like my biological mother. Sometimes she sounded as though she’d never left, and sometimes she sounded as though she’d never been near any part of the south. She seemed to be able to turn the accent on and off. She tended to turn it on for comforting people, and for threatening to kill them. Sometimes when I’m with Curtis, I see her in his face and wonder what kind of relative—what kind of mother-in-law—she would make. Today I think both Marcus and I were glad she was there. We needed to be close to someone with her kind of mothering strength.

The horrible noise ended. Maybe the poor man was dead and out of his misery. I hope so.

We never found him. We found human bones and animal bones. We found the rotting corpses of five people scattered among the boulders. We found the cold remains of a fire with a human femur and two human skulls lying among the ashes.

At last, we came home and wrapped our community wall around us and huddled in our illusions of security.

SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 22, 2026

No one has found my father. Almost every adult in the neighborhood has spent some time looking. Richard Moss didn’t, but his oldest son and daughter did. Wardell Parrish didn’t, but his sister and oldest nephew did. I don’t know what else people could have done. If I did know, I would be out doing it.

And yet nothing, nothing, nothing! The police never came up with any sign of him. He never turned up anywhere. He’s vanished, gone. Even the severed arm’s fingerprints weren’t his.

Every night since Wednesday, I’ve dreamed that horrible screaming. I’ve gone out twice more with teams hunting through the canyons. We’ve found nothing but more of the dead and the poorest of the living—people who are all staring eyes and visible bones. My own bones ached in empathy. Sometimes if I sleep for a while without hearing the screaming, I see these—the living dead. I’ve always seen them. I’ve never seen them.

A team I wasn’t with found a living child being eaten by dogs. The team killed the dogs, then watched, helpless as the boy died.

I spoke at services this morning. Maybe it was my duty. I don’t know. People came for church, all uncertain and upset, not knowing what they should do. I think they wanted to draw together, and they had years of habit drawing them together at our house on Sunday morning. They were uncertain and hesitant, but they came.

Both Wyatt Talcott and Jay Garfield offered to speak. Both did say a few words, both informally eulogizing my father, though neither admitted that that was what they were doing. I was afraid everyone would do that and the service would become an impossible impromptu funeral. When I stood up, it wasn’t just to say a couple of words. I meant to give them something they could take home—something that might make them feel that enough had been said for today.

I thanked them all for the ongoing—emphasize ongoing—efforts to find my father. Then…well, then I talked about perseverance. I preached a sermon about perseverance if an unordained kid can be said to preach a sermon. No one was going to stop me. Cory was the only one who might have tried, but Cory was in a kind of walking coma. She wasn’t doing anything she didn’t have to do.

So I preached from Luke, chapter eighteen, verses one through eight: the parable of the importunate widow. It’s one I’ve always liked. A widow is so persistent in her demands for justice that she overcomes the resistance of a judge who fears neither God nor man. She wears him down.

Moral: The weak can overcome the strong if the weak persist. Persisting isn’t always safe, but it’s often necessary.

My father and the adults present had created and maintained our community in spite of the scarcity and the violence outside. Now, with my father or without him, that community had to go on, hold together, survive. I talked about my nightmares and the source of those nightmares. Some people might not have wanted their kids to hear things like that, but I didn’t care. If Keith had known more, maybe he would still be alive. But I didn’t mention Keith. People could say what happened to Keith was his own fault. No one could say that about Dad. I didn’t want anyone to be able to say it about this community some day.

“Those nightmares of mine are our future if we fail one another,” I said, winding up. “Starvation, agony at the hands of people who aren’t human any more. Dismemberment. Death.

“We have God and we have each other. We have our island community, fragile, and yet a fortress. Sometimes it seems too small and too weak to survive. And like the widow in Christ’s parable, its enemies fear neither God nor man. But also like the widow, it persists. We persist. This is our place, no matter what.”

That was my message. I left it there, hanging before them with an unfinished feel to it. I could feel them expecting more, then realizing that I wasn’t going to say more, then biting down on what I had said.

At just the right moment, Kayla Talcott began an old song. Others took it up, singing slowly, but with feeling: “We shall not, we shall not be moved…”

I think this might have sounded weak or even pitiful somehow if it had been begun by a lesser voice. I think I might have sang it weakly. I’m only a fair singer. Kayla, on the other hand, has a big voice, beautiful, clear, and able to do everything she asks of it. Also, Kayla has a reputation for not moving unless she wants to.

Later, as she was leaving, I thanked her.

She looked at me. I’d grown past her years ago, and she had to look up. “Good job,” she said, and nodded and walked away toward her house. I love her.

I got other compliments today, and I think they were sincere. Most said, in one way or anoth

er, “You’re right,” and “I didn’t know you could preach like that,” and “Your father would be proud of you.”

Yeah, I hope so. I did it for him. He built this bunch of houses into a community. And now, he’s probably dead. I wouldn’t let them bury him, but I know. I’m no good at denial and self-deception. That was Dad’s funeral that I was preaching—his and the community’s. Because as much as I want all that I said to be true, it isn’t. We’ll be moved, all right. It’s just a matter of when, by whom, and in how many pieces.

13

❏ ❏ ❏

There is no end

To what a living world

Will demand of you.

EARTHSEED: THE BOOKS OF THE LIVING

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 19, 2026

TODAY REVEREND MATTHEW ROBINSON in whose church I was baptized came to preach my fathers funeral. Cory made the arrangements. There was no body, no urn. No one knows what happened to my father. Neither we nor the police have been able to find out. We’re sure he’s dead. He would find a way to come home if he were alive, so we’re certain he’s dead.

No, we’re not certain. We’re not certain at all. Is he sick somewhere? Hurt? Held against his will for who knows what reason by who knows what monsters?

This is worse than when Keith died. So much worse. As horrible as that was, we knew he was dead. Whatever he suffered, we knew he wasn’t suffering any more. Not in this world, anyway. We knew. Now, we don’t know anything. He is dead. But we don’t know!

The Dunns must of felt this when Tracy vanished. Crazy as they are, crazy as she was, they must have felt this. What do they feel now? Tracy never came back. If she’s not dead, what must be happening to her outside? A girl alone only faced one kind of future outside. I intend to go out posing as a man when I go.

How will they feel when I go? I’ll be dead to them—to Cory, the boys, the neighborhood. They’ll hope I’m dead, considering the supposed alternative. Thank Dad for my tallness and my strength.

Patternmaster

Patternmaster Survivor

Survivor Clay's Ark

Clay's Ark Bloodchild and Other Stories

Bloodchild and Other Stories Parable of the Sower

Parable of the Sower Wild Seed

Wild Seed Fledgling

Fledgling Unexpected Stories

Unexpected Stories Kindred

Kindred Lilith's Brood: Dawn / Adulthood Rites / Imago

Lilith's Brood: Dawn / Adulthood Rites / Imago Adulthood Rites

Adulthood Rites Mind of My Mind

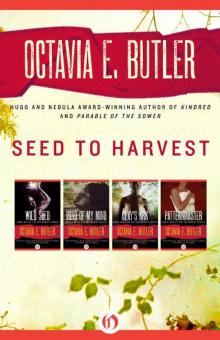

Mind of My Mind Seed to Harvest

Seed to Harvest Lilith's Brood: Dawn, Adulthood Rites, and Imago (Xenogenesis Trilogy)

Lilith's Brood: Dawn, Adulthood Rites, and Imago (Xenogenesis Trilogy) Bloodchild

Bloodchild Seed to Harvest: Wild Seed, Mind of My Mind, Clay's Ark, and Patternmaster (Patternist)

Seed to Harvest: Wild Seed, Mind of My Mind, Clay's Ark, and Patternmaster (Patternist)