- Home

- Octavia E. Butler

Parable of the Sower Page 7

Parable of the Sower Read online

Page 7

“Make sure they see you if you get first watch,” Dad said. “The sight of you will remind them that there will be watchers all through the night. We don’t want any of them mistaking you for thieves.”

Sensible. People go to bed soon after dark to save electricity, but between dinner and darkness they spend time on their porches or in their yards where it isn’t so hot. Some listen to their radio on front or back porches. Now and then people get together to play music, sing, play board games, talk, or get out on the paved part of the street for volleyball, touch football, basketball, or tennis. People used to play baseball, but we just can’t afford what that costs in windows. A few people just find a corner and read a book while there’s still daylight. It’s a good, comfortable, recreational time. What a pity to spoil it with reminders of reality. But it can’t be helped.

“What will you do if you catch a thief?” Cory asked my father before he went out. He was on the second shift, and he and Cory were having a rare cup of coffee together in the kitchen while he waited. Coffee was for special occasions. I couldn’t miss the good smell of it in my room where I lay awake.

I eavesdrop. I don’t put drinking glasses to walls or crouch with my ear against doors, but I do often lie awake long after dark when we kids are all supposed to be asleep. The kitchen is across the hall from my room, the dining room is nearby at the end of the hall, and my parents’ room is next door. The house is old and well insulated. If there’s a shut door between me and the conversation, I can’t hear much. But at night with all or most of the lights out, I can leave my door open a crack, and if other doors are also open, I can hear a lot. I learn a lot.

“We’ll chase him off, I hope,” Dad said. “We’ve agreed to that. We’ll give him a good scare and let him know there are easier ways to get a dollar.”

“A dollar…?”

“Yes, indeed. Our thieves didn’t steal all that food because they were hungry. They stripped those trees—took everything they could.”

“I know,” Cory said. “I took some lemons and grapefruits to both the Hsus and the Wyatts today and told them they could pick from our trees when they needed more. I took them some seed, too. They both had a lot of young plants trampled, but this early in the season, they should be able to repair the damage.”

“Yes.” My father paused. “But you see my point. People steal that way for money. They’re not desperate. Just greedy and dangerous. We might be able to scare them into looking for easier pickings.”

“But what if you can’t?” Cory asked, almost whispering. Her voice fell so low that I was afraid I would miss something.

“If you can’t, will you shoot them?”

“Yes,” he said.

“…yes?” she repeated in that same small voice. “Just…‘yes?’” She was like Joanne all over again—denial personified. What planet do people like that live on?

“Yes,” my father said.

“Why!”

There was a long silence. When my father spoke again, his own voice had gone very soft. “Baby, if these people steal enough, they’ll force us to spend more than we can afford on food—or go hungry. We live on the edge as it is. You know how hard things are.

“But…couldn’t we just call the police?”

“For what? We can’t afford their fees, and anyway, they’re not interested until after a crime has been committed. Even then, if you call them, they won’t show up for hours—maybe not for two or three days.”

“I know.”

“What are you saying then? You want the kids to go hungry? You want thieves coming into the house once they’ve stripped the gardens?”

“But they haven’t done that.”

“Of course they have. Mrs. Sims was only their latest victim.”

“She lived alone. We always said she shouldn’t do that.”

“You want to trust them not to hurt you or the kids just because there are seven of us? Baby, we can’t live by pretending this is still twenty or thirty years ago.”

“But you could go to jail!” She was crying—not sobbing, but speaking with that voice-full-of-tears that she can manage sometimes.

“No,” Dad said. “If we have to shoot someone, we’re together in it. After we’ve shot him we carry him into the nearest house. It’s still legal to shoot housebreakers. After that we do a little damage and get our stories straight.”

Long, long silence. “You could still get in trouble.”

“I’ll risk it.”

Another long silence. “‘Thou shalt not kill,’” Cory whispered.

“Nehemiah four,” Dad said. “Verse 14.”

There was nothing more. A few minutes later, I heard Dad leave. I waited until I heard Cory go to her room and shut the door. Then I got up, shut my door, moved my lamp so the light wouldn’t show under the door, then turned it on and opened my grandmother’s Bible. She had had a lot of Bibles and Dad had let me keep this one.

Nehemiah, chapter four, Verse 14: “And I looked and rose up and said unto the nobles, and to the rulers, and to the rest of the people, be not afraid of them: remember the Lord which is great and terrible, and fight for your brethren, your sons, and your daughters, your wives and your houses.”

Interesting. Interesting that Dad had that verse ready, and that Cory recognized it. Maybe they’ve had this conversation before.

SATURDAY, MARCH 15, 2025

It’s official.

Now we have a regular neighborhood watch—a roster of people from every household who are over eighteen, good with guns—their own and others—and considered responsible by my father and by the people who have already been patrolling the neighborhood. Since none of the watchers have ever been cops or security guards, they’ll go on working in pairs, watching out for each other as well as for the neighborhood. They’ll use whistles to call for help if they need it. Also, they’ll meet once a week to read, discuss, and practice martial arts and shoot-out techniques. The Montoyas will give their martial arts classes, all right, but not at my suggestion. Old Mr. Hsu is having back problems, and he won’t be teaching anything for a while, but the Montoyas seem to be enough. I plan to sit in on the classes as often as I can stand to share everyone’s practice pains.

Dad has collected all his books from me this morning. All I have left are my notes. I don’t mind. Thanks to the garden thieves, people are preparing themselves for the worst. I feel almost grateful to the thieves.

They haven’t come back, by the way—our thieves. When they do, we should be able to give them something they don’t expect.

SATURDAY, MARCH 29, 2025

Our thieves paid us another visit last night.

Maybe they weren’t the same ones, but their intentions were the same: To take away what someone else has sweated to grow and very much needs.

This time they were after Richard Moss’s rabbits. Those rabbits are the neighborhood’s only livestock except for some chickens the Cruz and Montoya families tried to raise a few years ago. Those were stolen as soon as they were old enough to make noise and let outsiders know they were there. The Moss rabbits have been our secret until this year when Richard Moss insisted on selling meat and whatever his wives could make from raw or tanned rabbit hides out beyond the wall. The Mosses had been selling to us all along, of course, meat, hides, fertilizer, everything except live rabbits. Those he hoarded as breeding stock. But now, stubborn, arrogant, and greedy, he had decided he could earn more if he peddled his merchandise outside. So, now the word is out on the street about the damned rabbits, and last night someone came to get them.

The Moss rabbit house is a converted three-car garage added to the property in the 1980s according to Dad. It’s hard to believe any household once had three cars, and gas fueled cars at that. But I remember the old garage before Richard Moss converted it. It was huge with three black oil spots on the floor where three cars had once been housed. Richard Moss repaired the walls and roof, put in windows for cross ventilation, and in general, made the place a

lmost fit for people to live in. In fact, it’s much better than what a lot of people live in now on the outside. He built rows and tiers of cages—hutches—and put in more electric lights and ceiling fans. The fans can be made to work on kid power. He’s hooked them up to an old bicycle frame, and every Moss kid who’s old enough to manage the pedals sooner or later gets drafted into powering the fans. The Moss kids hate it, but they know what they’ll get if they don’t do it.

I don’t know how many rabbits the Mosses have now, but it seems they’re always killing and skinning and doing disgusting things to pelts. Even a little monopoly is worth a lot of trouble.

The two thieves had managed to stuff 13 rabbits into canvas sacks by the time our watchers spotted them. The watchers were Alejandro Montoya and Julia Lincoln, one of Shani Yannis’s sisters. Mrs. Montoya has two kids sick with the flu so she’s off the watch roster for a while.

Mrs. Lincoln and Mr. Montoya followed the plan that the group of watchers had put together at their meetings. Without a word of command or warning, they fired their guns into the air two or three times each, at the same time, blowing their whistles full blast. They kept to cover, but inside the Moss house, someone woke up and turned on the rabbit house lights. That could have been a lethal mistake for the watchers, but they were hidden behind pomegranate bushes.

The two thieves ran like rabbits.

Abandoning sacks, rabbits, pry bars, a long coil of rope, wire cutters, and even an excellent long aluminum ladder, they scrambled up that ladder and over the wall in seconds. Our wall is three meters high and topped off with pieces of broken glass as well as the usual barbed wire and the all but invisible Lazor wire. All the wire had been cut in spite of our efforts. What a pity we couldn’t afford to electrify it or set other traps. But at least the glass—the oldest, simplest of our tricks—had gotten one of them. We found a broad stream of dried blood down the inside of the wall this morning.

We also found a Glock 19 pistol where one of the thieves had dropped it. Mrs. Lincoln and Mr. Montoya could have been shot. If the thieves hadn’t been scared out of their minds, there could have been a gun battle. Someone in the Moss house or a neighboring house could have been hurt or killed.

Cory went after Dad about that once they were alone in the kitchen tonight.

“I know,” Dad said. He sounded tired and miserable. “Don’t think we haven’t thought about those things. That’s why we want to scare the thieves away. Even shooting into the air isn’t safe. Nothing’s safe.”

“They ran away this time, but they won’t always run.”

“I know.”

“So what, then? You protect rabbits or oranges, and maybe get a child killed?”

Silence.

“We can’t live this way!” Cory shouted. I jumped. I’ve never heard her sound like that before.

“We do live this way,” Dad said. There was no anger in his voice, no emotional response at all to her shouting. There was nothing. Weariness. Sadness. I’ve never heard him sound so tired, so…almost beaten. And yet he had won. His idea had beaten off a pair of armed thieves without our having to hurt anyone. If the thieves had hurt themselves, that was their problem.

Of course they would come back, or others would come. That would happen no matter what. And Cory was right. The next thieves might not lose their guns and run away. So what? Should we lie in our beds and let them take all we had and hope they were content with stripping our gardens? How long does a thief stay content? And what’s it like to starve?

“We couldn’t make it without you,” Cory was saying. She wasn’t shouting now. “That could have been you out there, facing criminals. Next time it might be you. You could be shot, protecting the neighbors’ rabbits.”

“Did you notice,” Dad said, “that every off-duty watcher answered the whistles last night? They came out to defend their community.”

“I don’t care about them! It’s you I’m worried about!”

“No,” he said. “We can’t think that way any more. Cory, there’s nobody to help us but God and ourselves. I protect Moss’s place in spite of what I think of him, and he protects mine, no matter what he thinks of me. We all look out for one another.” He paused. “I’ve got plenty of insurance. You and the kids should be able to make it all right if—”

“No!” Cory said. “Do you think that’s all it is? Money? Do you think—?”

“No, Babe. No.” Pause. “I know what it is to be left alone. This is no world to be alone in.”

There was a long silence, and I didn’t think they would say any more. I lay on my bed, wondering if I should get up and shut my door so I could turn on my lamp and write. But there was a little more.

“What are we supposed to do if you die?” she demanded, and I think she was crying. “What do we do if they shoot you over some damn rabbits?”

“Live!” Dad said. “That’s all anybody can do right now. Live. Hold out. Survive. I don’t know whether good times are coming back again. But I know that won’t matter if we don’t survive these times.”

That was the end of their talk. I lay in the dark for a long time, thinking about what they had said. Cory was right again. Dad might get hurt. He might get killed. I don’t know how to think about that. I can write about it, but I don’t feel it. On some deep level, I don’t believe it. I guess I’m as good at denial as anyone.

So Cory is right, but it doesn’t matter. And Dad is right, but he doesn’t go far enough. God is Change, and in the end, God prevails. But God exists to be shaped. It isn’t enough for us to just survive, limping along, playing business as usual while things get worse and worse. If that’s the shape we give to God, then someday we must become too weak—too poor, too hungry, too sick—to defend ourselves. Then we’ll be wiped out.

There has to be more that we can do, a better destiny that we can shape. Another place. Another way. Something!

7

❏ ❏ ❏

We are all Godseed, but no more or less so than any other aspect of the universe, Godseed is all there is—all that Changes. Earthseed is all that spreads Earthlife to new earths. The universe is Godseed. Only we are Earthseed. And the Destiny of Earthseed is to take root among the stars.

EARTHSEED: THE BOOKS OF THE LIVING

SATURDAY, APRIL 26, 2025

SOMETIMES NAMING A THING—giving it a name or discovering its name—helps one to begin to understand it. Knowing the name of a thing and knowing what that thing is for gives me even more of a handle on it.

The particular God-is-Change belief system that seems right to me will be called Earthseed. I’ve tried to name it before. Failing that, I’ve tried to leave it unnamed. Neither effort has made me comfortable. Name plus purpose equals focus for me.

Well, today, I found the name, found it while I was weeding the back garden and thinking about the way plants seed themselves, windborne, animalborne, waterborne, far from their parent plants. They have no ability at all to travel great distances under their own power, and yet, they do travel. Even they don’t have to just sit in one place and wait to be wiped out. There are islands thousands of miles from anywhere—the Hawaiian Islands, for example, and Easter Island—where plants seeded themselves and grew long before any humans arrived.

Earthseed.

I am Earthseed. Anyone can be. Someday, I think there will be a lot of us. And I think we’ll have to seed ourselves farther and farther from this dying place.

I’ve never felt that I was making any of this up—not the name, Earthseed, not any of it. I mean, I’ve never felt that it was anything other than real: discovery rather than invention, exploration rather than creation. I wish I could believe it was all supernatural, and that I’m getting messages from God. But then, I don’t believe in that kind of God. All I do is observe and take notes, trying to put things down in ways that are as powerful, as simple, and as direct as I feel them. I can never do that. I keep trying, but I can’t. I’m not good enough as a writer or poet or whatever it is I need to be

. I don’t know what to do about that. It drives me frantic sometimes. I’m getting better, but so slowly.

The thing is, even with my writing problems, every time I understand a little more, I wonder why it’s taken me so long—why there was ever a time when I didn’t understand a thing so obvious and real and true.

Here’s the only puzzle in it all, the only paradox, or bit of illogic or circular reasoning or whatever it should be called:

Why is the universe?

To shape God.

Why is God?

To shape the universe.

I can’t get rid of it. I’ve tried to change it or dump it, but I can’t. I cannot. It feels like the truest thing I’ve ever written. It’s as mysterious and as obvious as any other explanation of God or the universe that I’ve ever read, except that to me the others feel inadequate, at best.

All the rest of Earthseed is explanation—what God is, what God does, what we are, what we should do, what we can’t help doing… Consider: Whether you’re a human being, an insect, a microbe, or a stone, this verse is true.

All that you touch,

You Change.

All that you Change,

Changes you.

The only lasting truth

Is Change.

God

Is Change.

I’m going to go through my old journals and gather the verses I’ve written into one volume. I’ll put them into one of the exercise notebooks that Cory hands out to the older kids now that there are so few computers in the neighborhood. I’ve written plenty of useless stuff in those books, getting my high school work out of the way. Now I’ll put one to better use. Then, someday when people are able to pay more attention to what I say than to how old I am, I’ll use these verses to pry them loose from the rotting past, and maybe push them into saving themselves and building a future that makes sense.

Patternmaster

Patternmaster Survivor

Survivor Clay's Ark

Clay's Ark Bloodchild and Other Stories

Bloodchild and Other Stories Parable of the Sower

Parable of the Sower Wild Seed

Wild Seed Fledgling

Fledgling Unexpected Stories

Unexpected Stories Kindred

Kindred Lilith's Brood: Dawn / Adulthood Rites / Imago

Lilith's Brood: Dawn / Adulthood Rites / Imago Adulthood Rites

Adulthood Rites Mind of My Mind

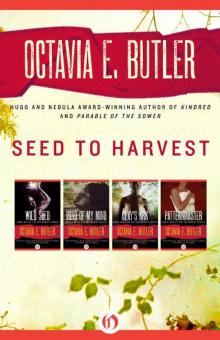

Mind of My Mind Seed to Harvest

Seed to Harvest Lilith's Brood: Dawn, Adulthood Rites, and Imago (Xenogenesis Trilogy)

Lilith's Brood: Dawn, Adulthood Rites, and Imago (Xenogenesis Trilogy) Bloodchild

Bloodchild Seed to Harvest: Wild Seed, Mind of My Mind, Clay's Ark, and Patternmaster (Patternist)

Seed to Harvest: Wild Seed, Mind of My Mind, Clay's Ark, and Patternmaster (Patternist)